By Larry Clinton, Sausalito Historical Society

William A. Coulter was considered one of the foremost artists on San Francisco Bay. He was born in 1849 in what is today Northern Ireland, where his father was captain in the Coast Guard. According to the website for Christopher Queen Galleries, which has an extensive collection of Early California paintings:

“At age 13 Coulter went to sea and learned every detail of the ships on which he sailed. He had a natural gift for drawing and color and during his off-duty hours aboard ship he sketched and painted. After arriving in San Francisco in 1869, he worked as a sailmaker while continuing to paint in his leisure and by 1874 was regularly exhibiting with the San Francisco Art Association. By 1890 he was living in Sausalito in a house that was just a few feet from the water.”

In 1980, this paper ran a series of sketches by Coulter from the Historical Society collection, along with a plea from SHS founder Jack Tracy, for more information on him. Nine readers replied, and one sent along a biographical sketch from the New York Times almost 45 years previously, at the time of his death. Here is an excerpt from that biography:

“While living in California, Coulter made two trips to Europe and four to the Hawaiian Islands. The rest of his time was spent in the Bay area, usually on the sunporch of his Sausalito home where he often watched the ships come in and out of the harbor. Coulter painted more than 5000 ocean scenes on canvas during his 60 year career. He always worked from memory except when special details were needed. “

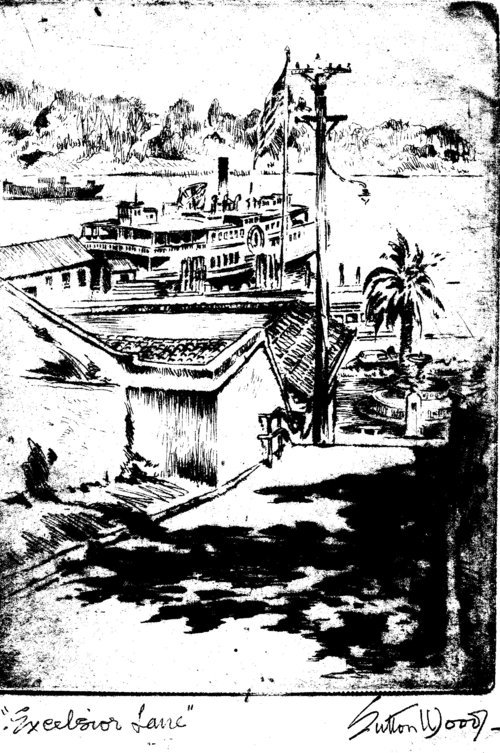

During the course of his life, his paintings chronicled the history of shipping and navigation in the San Francisco and San Pablo bays. In the late 1870s, he went to Europe to study with marine artists. In 1896, he joined the art staff of the San Francisco Call as their waterfront artist. His pen-and-ink drawings appeared daily until the disaster of 1906.

COURTESY PHOTO

William A. Coulter at his easel

Between 1909 and 1920, he spent two years on scaffolding while painting five 16-by-18-foot murals for the Assembly Room of the Merchants Exchange Building. His painting of the Golden Gate was reproduced on a U.S. postage stamp in 1923.

In 1935, a year before his death and five years after his retirement at age 80, Coulter held a one-man exhibit in San Francisco showing the 100 pictures he had completed since his retirement. Among that final collection was a modern scene of the Golden Gate Bridge as it stretched from near his home to San Francisco.

Coulter resided in Sausalito until his death on March 13, 1936, at the age of 87.

In November 1943, the 144th Liberty ship launched at the Permanente Metals Corporation shipyard in Richmond was christened the "S.S. William A. Coulter,” after the famous marine artist who his most productive years in Sausalito. His daughter Helen was sponsor at the launching.